WP_Query Object

(

[query] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 23

[1] => 65

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 8094

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

)

[query_vars] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 23

[1] => 65

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 8094

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

[error] =>

[m] =>

[p] => 0

[post_parent] =>

[subpost] =>

[subpost_id] =>

[attachment] =>

[attachment_id] => 0

[name] =>

[pagename] =>

[page_id] => 0

[second] =>

[minute] =>

[hour] =>

[day] => 0

[monthnum] => 0

[year] => 0

[w] => 0

[category_name] => meditation_mindfulness

[tag] =>

[cat] => 23

[tag_id] =>

[author] =>

[author_name] =>

[feed] =>

[tb] =>

[paged] => 0

[meta_key] =>

[meta_value] =>

[preview] =>

[s] =>

[sentence] =>

[title] =>

[fields] =>

[menu_order] =>

[embed] =>

[category__not_in] => Array

(

)

[category__and] => Array

(

)

[post__in] => Array

(

)

[post_name__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__not_in] => Array

(

)

[tag__and] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__in] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__and] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__in] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__not_in] => Array

(

)

[author__in] => Array

(

)

[author__not_in] => Array

(

)

[search_columns] => Array

(

)

[suppress_filters] =>

[cache_results] => 1

[update_post_term_cache] => 1

[update_menu_item_cache] =>

[lazy_load_term_meta] => 1

[update_post_meta_cache] => 1

[post_type] =>

[nopaging] =>

[comments_per_page] => 50

[no_found_rows] =>

[order] => DESC

)

[tax_query] => WP_Tax_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

[0] => Array

(

[taxonomy] => category

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 23

[1] => 65

)

[field] => term_id

[operator] => IN

[include_children] =>

)

)

[relation] => AND

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

[0] => wp_term_relationships

)

[queried_terms] => Array

(

[category] => Array

(

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 23

[1] => 65

)

[field] => term_id

)

)

[primary_table] => wp_posts

[primary_id_column] => ID

)

[meta_query] => WP_Meta_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

)

[relation] =>

[meta_table] =>

[meta_id_column] =>

[primary_table] =>

[primary_id_column] =>

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

)

[clauses:protected] => Array

(

)

[has_or_relation:protected] =>

)

[date_query] =>

[request] =>

SELECT SQL_CALC_FOUND_ROWS wp_posts.ID

FROM wp_posts LEFT JOIN wp_term_relationships ON (wp_posts.ID = wp_term_relationships.object_id)

WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.ID NOT IN (8094) AND (

wp_term_relationships.term_taxonomy_id IN (23,65)

) AND ((wp_posts.post_type = 'post' AND (wp_posts.post_status = 'publish' OR wp_posts.post_status = 'acf-disabled')))

AND ID NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('','employee')

AND `post_id` NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('' )))

GROUP BY wp_posts.ID

ORDER BY wp_posts.post_date DESC

LIMIT 0, 50

[posts] => Array

(

[0] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8641

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_content] =>

During a particularly hard break-up in my 20s, a friend advised me, “The more present you are during this process, the bigger the present you’ll get out of it.” And though I barely understood what that meant, I gave it a try and an odd thing happened. I saw that I was choosing the big, dramatic grieving process I was going through. And that meant it was optional.

In The Art of Presence, Eckhart Tolle says, “Through thought you cannot possibly grasp what presence is.” But he gives some clues to point us in the right direction. He says it’s there, “when you’re not thinking about the last moment, or looking to the next one.” And he uses phrases like “a state of relaxed alertness” and “a spacious stillness,” to describe it.

Thich Nhat Hanh said, “The most precious gift we can offer others is our presence.”

Our presence is tremendously rare and hugely valuable. Especially in this age of epidemic distraction, it’s increasingly difficult and uncommon to choose a voluntary time-out from technology, data, and our own mental analysis. But unlike the artificial value of a coin that accidentally got stamped with a head on both sides, our presence can do for us what nothing else can. And we can make it more abundant by simply choosing it.

Although it may not put food in our belly, most other problems disappear with presence. The need to fix or relive the past disappears. The need to avoid certain unwanted events in the future disappears. Even if we're working on something now that will benefit us in the future, with our presence, we work on it now in order to work on it now. And that’s enough.

The allure of distraction, which so often threatens our presence, dissolves when we practice being present. Do you know the word obviate? I like to write using words that almost everyone understands, but there’s only one word I can think of that means “to make unnecessary,” and that word is obviate. Learning to deepen our presence obviates the urge for distraction and mental departure from our current reality.

With presence, we perceive all kinds of intelligence and detail that we’re otherwise deaf and blind to. We know when to eat and when to stop eating. We know how to move our body in a way that doesn’t cause pain or injury. Our work becomes more interesting. Our relationships become healthier. We listen better and we feel heard.

With two kids, my presence is requested almost incessantly. I hear the word Papa at least 100 times a day. Often, I hear it ten or more times in quick succession. We all yearn for someone’s total presence with us. These are the moments of connection between what is the same in both of us. Presence uncovers what’s real in this moment. And that’s refreshing, exciting, and affirming.

When we’re all so busy that we see time as a commodity, it can seem that giving our presence to someone else is like giving away our treasure. But are we actually giving something away?

Of course not. When we “give” our presence we gain the present. To withhold our presence means both we and the other person miss out.

So, how can you learn to be more present? It takes practice. If you’re new to this, I don’t recommend making a goal like, “I’m going to be more present from now on.” I don’t want to discourage you, I just want you to be realistic about what you’re up against – a lifetime of habits and a sea of tantalizing distractions.

Try something a bit less ambitious, such as this: Once a day, as you begin some activity – whether it’s buying groceries, playing Candyland, eating a meal, and listening to a friend’s problems – select this activity as an exercise in presence. In your mind, identify what exactly you’re doing – “I’m vacuuming the floor” – and devote yourself to that. Don’t run away in the middle of the activity. This means don’t pick up your phone, don’t depart in your mind to explore other thoughts and ideas, don’t visit the past, don’t anticipate what’s next, don’t judge. Just dwell in the present. Be saturated by the present. Feel everything. Accept everything. And let each next moment come.

Over time, quicker than you might think, you’ll start regaining your attention. You’ll be able to focus on something for more than five seconds. You’ll begin to yearn for this, which will make your practice much easier. And as you start willingly selecting more and more moments to be completely present, you’ll experience an unending offering of presents.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => A Free Pile of Presents Just for You

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => a-free-pile-of-presents-just-for-you

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8641

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[1] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8421

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2021-11-27 00:28:59

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-11-27 00:28:59

[post_content] =>

There was a lot of interest in the article I wrote last month called “How to Bounce Forward from Adversity” in which I discussed positive psychology. Whereas traditional psychology has focused primarily on helping unwell individuals to get to a state of normal functioning, positive psychology explores how we can go beyond “normal” to optimize wellbeing and life satisfaction.

Today I’m going to share some of the most effective ways to do this. The core elements come from Martin Seligman, sometimes considered the founder positive psychology. Seligman is known for the PERMA model of wellbeing, which stands for: Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Achievement. We’ll look at these and some valuable additions from other psychologists.

Positive Emotions: This is as much a measure of optimal wellbeing as it is a means. Seligman emphasizes that seeking positive emotions alone isn’t especially effective, but that fully experiencing positive emotions is vital.

If positive emotions aren’t a prominent part of your psychological landscape, it’s worth looking and feeling into why. I believe positive emotions are part of our native state as humans, an expression of fundamental wellbeing, regardless of circumstances such as socioeconomic status. When they’re not naturally present, this tends to signal that there’s something in the way – such as limiting beliefs about one’s ability or deserving of happiness. We can change this.

Engagement: Having a sense of engagement, in which we may lose track of time and become completely absorbed in something we enjoy and excel at, is an important piece of wellbeing. It’s hard to have a developed sense of wellbeing if you are not truly engaged in anything you do

Psychologists Fred Bryant and Joseph Veroff build on these first two methods through their model of positive experience called Savoring. Here’s how to savor fully and get the most out of your positive experiences:

- Sharing: find other people to share the experience and tell them how much you value it. According to Black Dog Institute, this is the strongest predictor of the level of someone’ pleasure.

- Memory building: do things to crystalize and save the moment, such as intentionally take mental photographs, keeping a souvenir of the event, and reminiscing about it later with others.

- Self-congratulation: this is a hard one for many of us because it entails telling yourself what a good person you are and remembering everything you’ve done to get yourself to this point in your life.

- Sharpening perception: this is practice to encourage the imprinting of the experience in your consciousness. Pay close attention and try focusing on certain elements and blocking out others, like closing your eyes while listening to music.

- Absorption: allow yourself to become totally immersed, not thinking, just experiencing fully

Relationships: Study after study has shown that healthy relationships are the single most significant predictor of happiness and longevity. We are social creatures and our connections with others help us flourish. They give us opportunities to share, to help, to be heard, to be witnessed, to touch, to laugh, to be co-inspired. I have a homework assignment for you. Today I want you to call or visit someone you haven’t been in contact with for a while. Both of you will benefit from this.

Meaning: There are plenty of ways to experience positive emotions and good connections without meaning, but for most of us, especially as we get older, this factor starts to matter more. Sometimes we can even have a “meaningless crisis” where we suddenly feel that nothing in our life has real significance. If we’ve spent the last decade getting stoned and playing video games, maybe such a realization is pointing to a need for some changes. But for most people, it’s a matter of attitude adjustment more than a life overhaul.

For instance, doing the core values, gifts, and life purpose work in our Dreambook can help you get aligned with your meaning, which you then bring into whatever you do. An early mentor of mine, Matt Garrigan, used to say, “Life is meaningless. You add the meaning.” While that might sound kind of fatalistic, he meant it to be liberating. It underscores the power to choose our perspective.

Dr. Amy Wrzesniewski of Yale University writes about the distinctions between relating to your work as a job (you see your work as a means of income, a necessity), a career (you take a certain pride in what you do and hope to advance and succeed at it), or a calling (your work is a central, meaningful part of life and who you are, a forum for self-expression and gratification). These three orientations represent degrees of meaning, and a spectrum of overall life satisfaction. Being dedicated to something bigger than oneself brings to a special kind of fulfillment. Incidentally, Wrzesniewski emphasizes that the job itself is irrelevant to one’s orientation toward it. You could approach trash collection as a calling.

Achievement: In a world that sometimes hyper-focuses on achievement as the sole measure of a person’s worth, it’s easy to get the wrong idea about it and find ourselves unable to relax and play. But we need to strike a balance because accomplishing things, even small things, is essential to authentic wellbeing.

When we set out to do something and follow it through to completion we build confidence and self-trust, and it reinforces the feeling that we have some control over the trajectory of our work and overall life, which is another factor that yields greater wellbeing.

Play: Being able to play – doing something for no outcome other than play itself – is one I’d add to this list. Here’s an excerpt on play from our book, The Well Life:

George Bernard Shaw said, “We don’t stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing.” We know it’s hard to schedule time just for enjoyment, but play is important stuff. Playing and laughing are good for our cardiovascular health. They foster bonding with our family and friends. They’re relaxing. They promote development of social skills. They’re uplifting. They teach us cooperation. They help us learn to manage our emotions. They improve brain function, learning, and cognition. They relieve stress. They enhance healing. They stimulate creativity and problem solving. They keep us feeling youthful. Unfortunately, we tend to save playtime for after everything else is done. But it shouldn’t be seen as just a reward. Play is therapeutic.

Finally, one more that numerous others have added to PERMA is Vitality. Physical vitality and psychological wellness are interdependent. That’s not to say you can’t have one without the other, but many physical health factors such as high energy, good digestion, restful sleep, and adequate strength often translate to a better ability to do the other things on the list, as well as supporting a clear and open mind.

I encourage you to go through this list and choose one factor to dedicate yourself this coming week – ideally one that could use some attention. Set an intention to work on it each day, and write it down. At the end of each day, take a few minutes to reflect on (and, better yet, journal about) how this affected you.

Be well,

Peter

[post_title] => Use Positive Psychology to Get Happier and More Fulfilled

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => 8421

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2021-11-27 01:10:48

[post_modified_gmt] => 2021-11-27 01:10:48

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8421

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[2] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8686

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2022-06-23 23:13:57

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-06-23 23:13:57

[post_content] =>

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about the differences between acupuncture and “dry needling” to alleviate pain, and in that article I explained a bit about the phenomenon of myofascial trigger points. After I said I believe these are the cause of most of the physical pain humans experience, a number of readers asked me to explain more. For the science lovers out there, I’m going to dive deeper this week.

Besides the most common forms of pain, like lower back and headaches, I’ve had patients with digestive problems, sinus congestion, chest pain, ear ringing, numb hands, painful intercourse, acid reflux, vision changes, and other health issues that were eventually discovered to be due to myofascial trigger points. I believe everyone should know about them and how they work – it could save us a lot of time and worry.

Basically, a trigger point is a small, irritable region in a muscle (or the surrounding connective tissue – “fascia”) that stays stuck in a contracted state, making the muscle fibers taut. This can cause reduced muscle strength and range of motion, pain, numbness, itching, and other forms of dysfunction. Sometimes a trigger point feels like a palpable nodule or “knot,” but to untrained fingers they’re often tricky to find.

A unique property of trigger points is that they’re able to produce symptoms in other parts of the body – from a few inches to a couple feet away. For instance, there’s a trigger point that can form in the soleus muscle of the calf that’s capable of producing pain in the lower back. For this reason, the work of Janet Travell, MD and her colleague David Simons, MD, was groundbreaking. For each muscle in the body, they mapped where trigger points tend to form and what kinds of symptoms they cause.

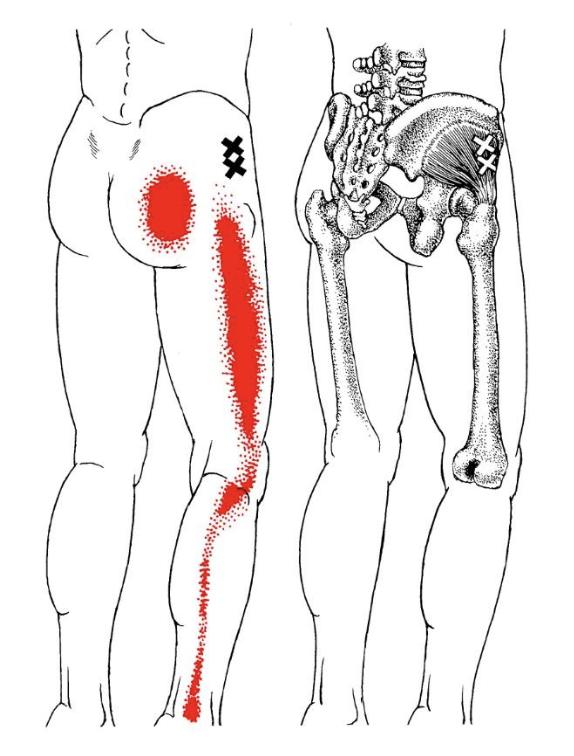

If you were experiencing pain along the outside of your leg, you might assume that something was wrong with that part of your leg, perhaps with the often-tight iliotibial band (IT band). But this diagram might be helpful. The X’s show where trigger points can occur in a muscle called gluteus minimus above the hip socket. The red shading shows the potential areas of pain that can result. You might not suspect this muscle because, as you can see, there’s no pain at the site of the problem!

There are a handful of mechanisms that can promote trigger point formation, such as irritation of nerves, chronic organ problems, nutritional deficiencies, and autoimmune disorders. Most often, though, the cause is trauma to our connective tissue. When a muscle is strained by being worked too hard, too fast, or beyond its natural range, there is frequently a sort of “recoil” that occurs as segments of the muscle fibers bunch up and remain that way.

This is especially common when someone works out without warming up; when someone does a very ambitious workout after not having exercised for a long time; when someone makes a sudden movement (like reaching out to catch something or trying to stop oneself from falling); and especially when someone does any of the above when in a state of diminished resilience (e.g, when stressed, upset, sleep deprived, eating poorly, etc.).

Even more commonly, the trauma is a form of “postural stress” that’s demanding on muscles in a way that’s difficult to perceive at the time – such as doing the same relatively motionless activity (like sitting at a desk or driving) for hours, days, months, or years. One possible mechanism is known as the “Cinderella hypothesis.” During static muscle exertion – holding a position for a long time, as dentists, musicians, typists, and others engaged in precision handwork do – the body tends to engage a certain group of small muscle fibers, called Cinderella fibers because they’re put to work first and are the last to be disengaged. Even though they’re not doing heavy lifting, these muscle fibers (often in the neck, shoulders, back, and forearms) are continually activated and overworked, which makes them susceptible to trigger point formation.

Whatever the cause, the result is that eventually the muscle never completely relaxes. Muscles are composed of numerous parallel fibers that work together to shorten (contraction of the muscle) and lengthen (the return of the muscle to its relaxed state). Within each of these fibers are many end-to-end contractile units called sarcomeres, and in the case of a trigger point, a group of sarcomeres gets “stuck” in a shortened state. This makes the affected fibers taut and often “stringy” feeling.

To make matters worse, the contracted region clamps down on tiny blood vessels causing local ischemia (inadequate blood supply), reducing in-flow of fresh, oxygenated blood and out-flow of toxins. This leads to a localized hypoxic state (not enough oxygen). The tissue pH changes, local metabolism is impaired, and fluid and waste products tend to build up in the area. This combination of factors ultimately activates pain receptors – it starts to hurt – and when this happens you use the affected muscle less.

Instead, you overload “synergists” – nearby helper muscles. The body makes the surrounding musculature tense as a protective mechanism. Meanwhile, there’s a disruption of the balance between the affected muscles and their “antagonists” – those muscles that lengthen when the primary muscles shorten and vice-versa (for example, the triceps is an antagonist of the biceps). Altogether, this restricts natural movement of the original muscle, which just perpetuates the imbalance. Finally, with longstanding trigger points, the body may deposit gooey lubricant compounds called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) between these triggered muscle fibers, resulting in a gummy lump called a “myogelosis.”

The good news is that there are now books, charts, online tools, and practitioners that can help track down likely trigger points that may be implicated in your discomfort. I have such a tool in my online pain relief course, Live Pain Free, and I teach many approaches for deactivating trigger points.

The most basic methods involve simple mechanical disruption of this holding pattern. First, drink some water if you’re not well hydrated. Second, you or a friend can methodically feel around (ideally guided by a trigger point chart) for points that are sore, and ideally that reproduce the very sensation you’ve been experiencing. Third, maintain firm pressure on the epicenter of the point (with a finger, elbow, ball, or other tool) for about half a minute, consciously breathing into the area and intending to let it go, until there’s a palpable release. Then move on to all the other nearby points that are tight and tender and do the same.

This approach is called ischemic compression. By compressing the tissue enough to block blood flow, the body responds with reflex vasodilation, meaning it opens these vessels and flushes the tissue with a dramatic increase of blood. This will usually produce a significant improvement in the pain or dysfunction, though it will typically return sooner or later. These points tend to go from being active trigger points to “latent” trigger points, which have a certain “memory” (not the good kind of muscle memory) and are capable of getting reactivated. For this reason, persistence is important. The best results come from working on a trigger point consistently – usually from one to several short sessions per day (or less frequent if the sessions are intense) – and continuing for a while even after everything seems better.

As I said, this is a most basic approach, and while it’s often effective, sometimes a more nuanced intervention is required. There are many techniques that build on compression. We can replace fixed pressure with slow, deep strokes in the direction of the muscle fiber, as if re-lengthening this segment. We can work the trigger point back and forth across the direction of the muscle fibers. We can combine pressure on the trigger point with engagement of the affected muscle or antagonistic muscles. We can combine manual work on trigger points with topical herbs and/or internal herbs and nutrients that improve circulation and reduce inflammation. We can utilize release p

If you were experiencing pain along the outside of your leg, you might assume that something was wrong with that part of your leg, perhaps with the often-tight iliotibial band (IT band). But this diagram might be helpful. The X’s show where trigger points can occur in a muscle called gluteus minimus above the hip socket. The red shading shows the potential areas of pain that can result. You might not suspect this muscle because, as you can see, there’s no pain at the site of the problem!

There are a handful of mechanisms that can promote trigger point formation, such as irritation of nerves, chronic organ problems, nutritional deficiencies, and autoimmune disorders. Most often, though, the cause is trauma to our connective tissue. When a muscle is strained by being worked too hard, too fast, or beyond its natural range, there is frequently a sort of “recoil” that occurs as segments of the muscle fibers bunch up and remain that way.

This is especially common when someone works out without warming up; when someone does a very ambitious workout after not having exercised for a long time; when someone makes a sudden movement (like reaching out to catch something or trying to stop oneself from falling); and especially when someone does any of the above when in a state of diminished resilience (e.g, when stressed, upset, sleep deprived, eating poorly, etc.).

Even more commonly, the trauma is a form of “postural stress” that’s demanding on muscles in a way that’s difficult to perceive at the time – such as doing the same relatively motionless activity (like sitting at a desk or driving) for hours, days, months, or years. One possible mechanism is known as the “Cinderella hypothesis.” During static muscle exertion – holding a position for a long time, as dentists, musicians, typists, and others engaged in precision handwork do – the body tends to engage a certain group of small muscle fibers, called Cinderella fibers because they’re put to work first and are the last to be disengaged. Even though they’re not doing heavy lifting, these muscle fibers (often in the neck, shoulders, back, and forearms) are continually activated and overworked, which makes them susceptible to trigger point formation.

Whatever the cause, the result is that eventually the muscle never completely relaxes. Muscles are composed of numerous parallel fibers that work together to shorten (contraction of the muscle) and lengthen (the return of the muscle to its relaxed state). Within each of these fibers are many end-to-end contractile units called sarcomeres, and in the case of a trigger point, a group of sarcomeres gets “stuck” in a shortened state. This makes the affected fibers taut and often “stringy” feeling.

To make matters worse, the contracted region clamps down on tiny blood vessels causing local ischemia (inadequate blood supply), reducing in-flow of fresh, oxygenated blood and out-flow of toxins. This leads to a localized hypoxic state (not enough oxygen). The tissue pH changes, local metabolism is impaired, and fluid and waste products tend to build up in the area. This combination of factors ultimately activates pain receptors – it starts to hurt – and when this happens you use the affected muscle less.

Instead, you overload “synergists” – nearby helper muscles. The body makes the surrounding musculature tense as a protective mechanism. Meanwhile, there’s a disruption of the balance between the affected muscles and their “antagonists” – those muscles that lengthen when the primary muscles shorten and vice-versa (for example, the triceps is an antagonist of the biceps). Altogether, this restricts natural movement of the original muscle, which just perpetuates the imbalance. Finally, with longstanding trigger points, the body may deposit gooey lubricant compounds called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) between these triggered muscle fibers, resulting in a gummy lump called a “myogelosis.”

The good news is that there are now books, charts, online tools, and practitioners that can help track down likely trigger points that may be implicated in your discomfort. I have such a tool in my online pain relief course, Live Pain Free, and I teach many approaches for deactivating trigger points.

The most basic methods involve simple mechanical disruption of this holding pattern. First, drink some water if you’re not well hydrated. Second, you or a friend can methodically feel around (ideally guided by a trigger point chart) for points that are sore, and ideally that reproduce the very sensation you’ve been experiencing. Third, maintain firm pressure on the epicenter of the point (with a finger, elbow, ball, or other tool) for about half a minute, consciously breathing into the area and intending to let it go, until there’s a palpable release. Then move on to all the other nearby points that are tight and tender and do the same.

This approach is called ischemic compression. By compressing the tissue enough to block blood flow, the body responds with reflex vasodilation, meaning it opens these vessels and flushes the tissue with a dramatic increase of blood. This will usually produce a significant improvement in the pain or dysfunction, though it will typically return sooner or later. These points tend to go from being active trigger points to “latent” trigger points, which have a certain “memory” (not the good kind of muscle memory) and are capable of getting reactivated. For this reason, persistence is important. The best results come from working on a trigger point consistently – usually from one to several short sessions per day (or less frequent if the sessions are intense) – and continuing for a while even after everything seems better.

As I said, this is a most basic approach, and while it’s often effective, sometimes a more nuanced intervention is required. There are many techniques that build on compression. We can replace fixed pressure with slow, deep strokes in the direction of the muscle fiber, as if re-lengthening this segment. We can work the trigger point back and forth across the direction of the muscle fibers. We can combine pressure on the trigger point with engagement of the affected muscle or antagonistic muscles. We can combine manual work on trigger points with topical herbs and/or internal herbs and nutrients that improve circulation and reduce inflammation. We can utilize release points on the same acupuncture meridian as where the trigger point occurs - or complementary points on other parts of the body. And more.

If all of this sounds interesting and relevant to you, I encourage you to do a little research. It might well be the end of a problem you thought had no solution. And if you need more guidance, check out my online course, Live Pain Free, where I go deeper into trigger points and much, much more to help people get out of pain of all kinds.

While I said I believe trigger points are the cause of most of our physical pain, I think it’s worth mentioning there are usually even deeper causes, such as stress and withheld emotions, poor body mechanics, dehydration, and an inflammatory diet. Holistically addressing these issues will lead to a more complete resolution of the condition. Always look at the big picture.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => The Science Behind Our Pain: Inquiring Minds Want to Know

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-science-behind-our-pain-inquiring-minds-want-to-know

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2022-06-27 03:51:11

[post_modified_gmt] => 2022-06-27 03:51:11

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8686

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

)

[post_count] => 3

[current_post] => -1

[before_loop] => 1

[in_the_loop] =>

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8641

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_content] =>

During a particularly hard break-up in my 20s, a friend advised me, “The more present you are during this process, the bigger the present you’ll get out of it.” And though I barely understood what that meant, I gave it a try and an odd thing happened. I saw that I was choosing the big, dramatic grieving process I was going through. And that meant it was optional.

In The Art of Presence, Eckhart Tolle says, “Through thought you cannot possibly grasp what presence is.” But he gives some clues to point us in the right direction. He says it’s there, “when you’re not thinking about the last moment, or looking to the next one.” And he uses phrases like “a state of relaxed alertness” and “a spacious stillness,” to describe it.

Thich Nhat Hanh said, “The most precious gift we can offer others is our presence.”

Our presence is tremendously rare and hugely valuable. Especially in this age of epidemic distraction, it’s increasingly difficult and uncommon to choose a voluntary time-out from technology, data, and our own mental analysis. But unlike the artificial value of a coin that accidentally got stamped with a head on both sides, our presence can do for us what nothing else can. And we can make it more abundant by simply choosing it.

Although it may not put food in our belly, most other problems disappear with presence. The need to fix or relive the past disappears. The need to avoid certain unwanted events in the future disappears. Even if we're working on something now that will benefit us in the future, with our presence, we work on it now in order to work on it now. And that’s enough.

The allure of distraction, which so often threatens our presence, dissolves when we practice being present. Do you know the word obviate? I like to write using words that almost everyone understands, but there’s only one word I can think of that means “to make unnecessary,” and that word is obviate. Learning to deepen our presence obviates the urge for distraction and mental departure from our current reality.

With presence, we perceive all kinds of intelligence and detail that we’re otherwise deaf and blind to. We know when to eat and when to stop eating. We know how to move our body in a way that doesn’t cause pain or injury. Our work becomes more interesting. Our relationships become healthier. We listen better and we feel heard.

With two kids, my presence is requested almost incessantly. I hear the word Papa at least 100 times a day. Often, I hear it ten or more times in quick succession. We all yearn for someone’s total presence with us. These are the moments of connection between what is the same in both of us. Presence uncovers what’s real in this moment. And that’s refreshing, exciting, and affirming.

When we’re all so busy that we see time as a commodity, it can seem that giving our presence to someone else is like giving away our treasure. But are we actually giving something away?

Of course not. When we “give” our presence we gain the present. To withhold our presence means both we and the other person miss out.

So, how can you learn to be more present? It takes practice. If you’re new to this, I don’t recommend making a goal like, “I’m going to be more present from now on.” I don’t want to discourage you, I just want you to be realistic about what you’re up against – a lifetime of habits and a sea of tantalizing distractions.

Try something a bit less ambitious, such as this: Once a day, as you begin some activity – whether it’s buying groceries, playing Candyland, eating a meal, and listening to a friend’s problems – select this activity as an exercise in presence. In your mind, identify what exactly you’re doing – “I’m vacuuming the floor” – and devote yourself to that. Don’t run away in the middle of the activity. This means don’t pick up your phone, don’t depart in your mind to explore other thoughts and ideas, don’t visit the past, don’t anticipate what’s next, don’t judge. Just dwell in the present. Be saturated by the present. Feel everything. Accept everything. And let each next moment come.

Over time, quicker than you might think, you’ll start regaining your attention. You’ll be able to focus on something for more than five seconds. You’ll begin to yearn for this, which will make your practice much easier. And as you start willingly selecting more and more moments to be completely present, you’ll experience an unending offering of presents.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => A Free Pile of Presents Just for You

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => a-free-pile-of-presents-just-for-you

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2022-04-08 21:50:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8641

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[comment_count] => 0

[current_comment] => -1

[found_posts] => 148

[max_num_pages] => 3

[max_num_comment_pages] => 0

[is_single] =>

[is_preview] =>

[is_page] =>

[is_archive] => 1

[is_date] =>

[is_year] =>

[is_month] =>

[is_day] =>

[is_time] =>

[is_author] =>

[is_category] => 1

[is_tag] =>

[is_tax] =>

[is_search] =>

[is_feed] =>

[is_comment_feed] =>

[is_trackback] =>

[is_home] =>

[is_privacy_policy] =>

[is_404] =>

[is_embed] =>

[is_paged] =>

[is_admin] =>

[is_attachment] =>

[is_singular] =>

[is_robots] =>

[is_favicon] =>

[is_posts_page] =>

[is_post_type_archive] =>

[query_vars_hash:WP_Query:private] => d49dc54025c48f993f4a32e2b843f855

[query_vars_changed:WP_Query:private] =>

[thumbnails_cached] =>

[allow_query_attachment_by_filename:protected] =>

[stopwords:WP_Query:private] =>

[compat_fields:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => query_vars_hash

[1] => query_vars_changed

)

[compat_methods:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => init_query_flags

[1] => parse_tax_query

)

)