WP_Query Object

(

[query] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 25

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 7239

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

)

[query_vars] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 25

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 7239

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

[error] =>

[m] =>

[p] => 0

[post_parent] =>

[subpost] =>

[subpost_id] =>

[attachment] =>

[attachment_id] => 0

[name] =>

[pagename] =>

[page_id] => 0

[second] =>

[minute] =>

[hour] =>

[day] => 0

[monthnum] => 0

[year] => 0

[w] => 0

[category_name] => nutrition

[tag] =>

[cat] => 25

[tag_id] =>

[author] =>

[author_name] =>

[feed] =>

[tb] =>

[paged] => 0

[meta_key] =>

[meta_value] =>

[preview] =>

[s] =>

[sentence] =>

[title] =>

[fields] =>

[menu_order] =>

[embed] =>

[category__not_in] => Array

(

)

[category__and] => Array

(

)

[post__in] => Array

(

)

[post_name__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__not_in] => Array

(

)

[tag__and] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__in] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__and] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__in] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__not_in] => Array

(

)

[author__in] => Array

(

)

[author__not_in] => Array

(

)

[search_columns] => Array

(

)

[suppress_filters] =>

[cache_results] => 1

[update_post_term_cache] => 1

[update_menu_item_cache] =>

[lazy_load_term_meta] => 1

[update_post_meta_cache] => 1

[post_type] =>

[nopaging] =>

[comments_per_page] => 50

[no_found_rows] =>

[order] => DESC

)

[tax_query] => WP_Tax_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

[0] => Array

(

[taxonomy] => category

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 25

)

[field] => term_id

[operator] => IN

[include_children] =>

)

)

[relation] => AND

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

[0] => wp_term_relationships

)

[queried_terms] => Array

(

[category] => Array

(

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 25

)

[field] => term_id

)

)

[primary_table] => wp_posts

[primary_id_column] => ID

)

[meta_query] => WP_Meta_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

)

[relation] =>

[meta_table] =>

[meta_id_column] =>

[primary_table] =>

[primary_id_column] =>

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

)

[clauses:protected] => Array

(

)

[has_or_relation:protected] =>

)

[date_query] =>

[request] =>

SELECT SQL_CALC_FOUND_ROWS wp_posts.ID

FROM wp_posts LEFT JOIN wp_term_relationships ON (wp_posts.ID = wp_term_relationships.object_id)

WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.ID NOT IN (7239) AND (

wp_term_relationships.term_taxonomy_id IN (25)

) AND ((wp_posts.post_type = 'post' AND (wp_posts.post_status = 'publish' OR wp_posts.post_status = 'acf-disabled')))

AND ID NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('','employee')

AND `post_id` NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('' )))

GROUP BY wp_posts.ID

ORDER BY wp_posts.post_date DESC

LIMIT 0, 50

[posts] => Array

(

[0] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8850

[post_author] => 1

[post_date] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_content] =>

One of the earliest inspirations that prompted me to go into medicine was a book called The Science of Homeopathy by George Vithoulkas. Of all the many modalities of mainstream and alternative medicine, few are as widely used – or criticized – as homeopathy.

Most other medical systems are heteropathic or allopathic in their approach. Hetero means other or different, allo means opposite, and pathy means suffering or disease. So, both terms mean producing a condition that is incompatible with or antagonistic to the disease process. Today many people use the term “allopathic” in a negative sense to describe mainstream medicine, but if you take an anti-inflammatory herb such as turmeric for inflammation, or an antibacterial such as garlic for an infection, this is allopathic medicine.

Homeopathy is based on the idea that if a particular substance produces a certain reaction (e.g., ipecacuanha causes nausea and vomiting), minuscule quantities of that substance can treat that condition (e.g., homeopathic ipecacuanha alleviates nausea and vomiting). Homeo means like, so homeopathy means “like the disease” and it’s based on the principle that “like treats like.” Some other examples are the use of homeopathic coffee (Coffea cruda) to treat insomnia and agitation, homeopathic onion (Allium cepa) for red and watery eyes and nose, and homeopathic bee venom (Apis) for stings, swellings, and inflammation.

For what it’s worth, not all remedies work this way. In many cases, homeopathic preparations do the same thing the original substance does. The remedy Chamomilla, for instance, is homeopathic chamomile, and like the herb, it is used for digestive and emotional upset. Sometimes homeopathic versions are safer, gentler, more potent, or have a broader range of application. In the case of Chamomilla, it’s also used for teething, ear pain, and menstrual discomfort.

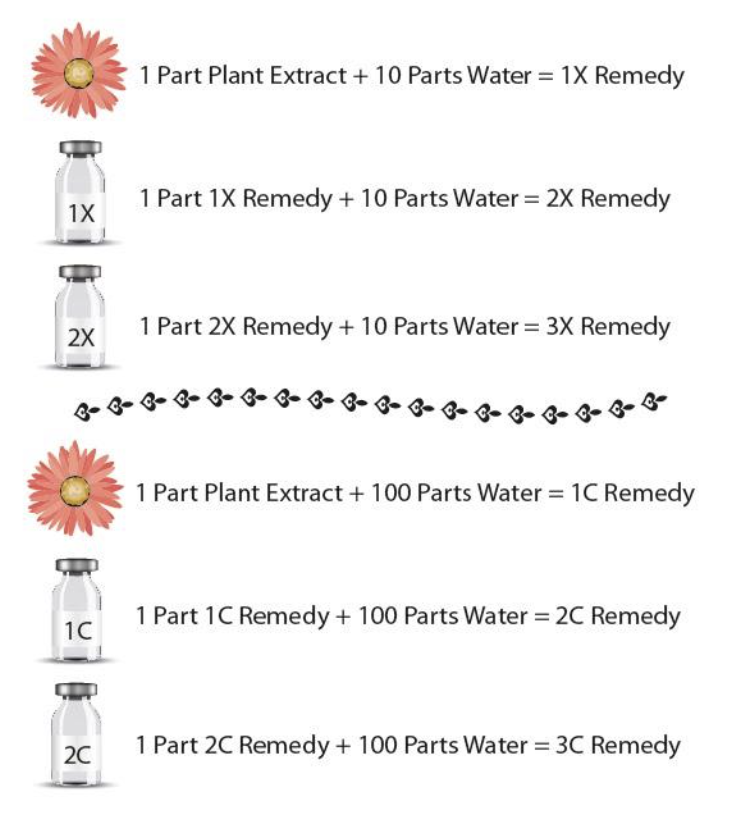

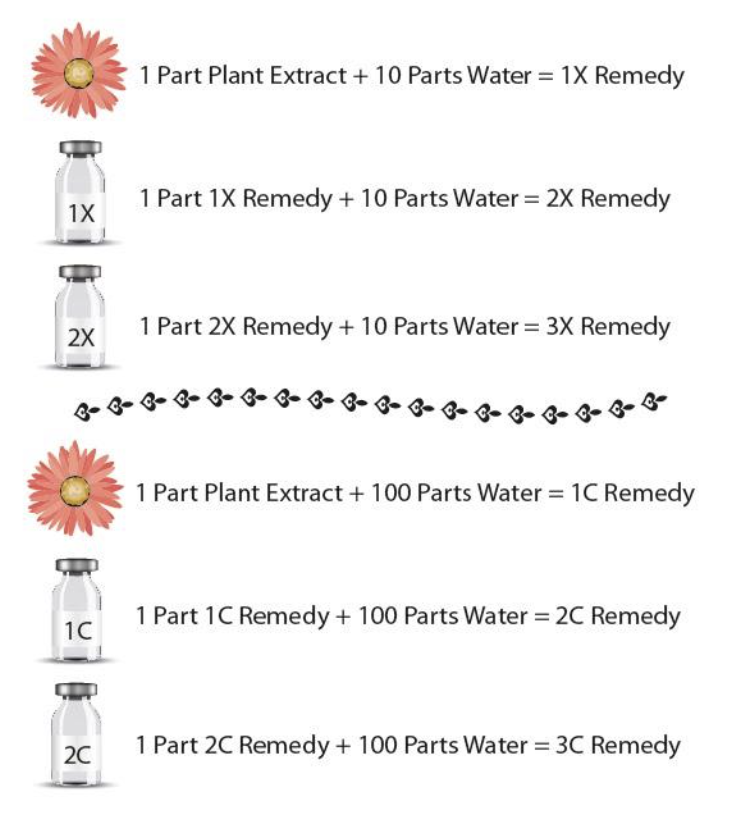

Homeopathic remedies are created through numerous successive dilutions of herbs, minerals, animal parts and occasionally other substances. When the original substance is diluted in ten parts of a solvent (water or alcohol), this is called an X dilution (X being the Roman numeral for ten). When the substance is diluted in one hundred parts of a solvent, this is a C dilution (C being the Roman numeral for hundred). Each time a dilution is made it is shaken in a specific way to transfer the substance to the solvent, and each successive dilution, though chemically weaker, is considered energetically more potent. I made this chart to explain the process:

Many homeopathic remedies are made from highly toxic substances, like arsenic or deadly nightshade. In these cases, the original substance is so highly diluted that the amount of toxin in a resulting pill or tincture is infinitesimal. Often, it’s unlikely that there is even a single molecule of the original substance in the resulting medicine. This is precisely why opponents of homeopathy argue that it’s worthless and call it pseudoscience.

As a scientist, I completely understand this stance, but in my opinion, what occurs in the preparation of a homeopathic remedy is something we don’t yet have the science to explain. I believe the substance leaves some kind of energetic imprint on the solvent it is diluted in. We know from Masaru Emoto’s research on water that various substances and even human intention are capable of leaving a lasting mark on water molecules that’s evidenced in the different forms of ice crystals it forms when frozen. I believe a similar process occurs through diluting and shaking a substance in water, even when the substance is eventually removed.

I must admit, my own experience with homeopathy has been hit-or-miss. I’ve taken numerous remedies that did nothing perceptible. As to whether I chose the wrong remedy or it wasn’t medicinally effective, I’ll never know. But I have also had cases in which homeopathics were remarkably effective.

This has been especially true with babies and animals, and these are cases we could assume are relatively free from the influence of the placebo effect since the recipients are presumably unaware that they’re getting medicine. In particular, I have repeatedly had the experience of giving homeopathic teething tablets to babies that were inconsolable, and within minutes they were peaceful and sleepy. As a parent, I don’t care what the mechanism is as long as it’s safe and it works.

The safety factor is significant, particularly for children, pregnant women, and elderly or frail people. Not only are homeopathics virtually free of side effects, they also tend to have zero “load” on the system. That is, they don’t make you feel like you’re on a drug. Sometimes this may come at the expense of strength (e.g., homeopathic Chamomilla doesn’t approach the potency of Xanax), but there are cases when the top priority is a clean experience. I find this to be especially true in anxiety, when making someone feel drugged can occasionally intensify the anxiety.

Have you tried homeopathy? What did you think? Share with us in the comments section. I would love to hear about your experience.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

Many homeopathic remedies are made from highly toxic substances, like arsenic or deadly nightshade. In these cases, the original substance is so highly diluted that the amount of toxin in a resulting pill or tincture is infinitesimal. Often, it’s unlikely that there is even a single molecule of the original substance in the resulting medicine. This is precisely why opponents of homeopathy argue that it’s worthless and call it pseudoscience.

As a scientist, I completely understand this stance, but in my opinion, what occurs in the preparation of a homeopathic remedy is something we don’t yet have the science to explain. I believe the substance leaves some kind of energetic imprint on the solvent it is diluted in. We know from Masaru Emoto’s research on water that various substances and even human intention are capable of leaving a lasting mark on water molecules that’s evidenced in the different forms of ice crystals it forms when frozen. I believe a similar process occurs through diluting and shaking a substance in water, even when the substance is eventually removed.

I must admit, my own experience with homeopathy has been hit-or-miss. I’ve taken numerous remedies that did nothing perceptible. As to whether I chose the wrong remedy or it wasn’t medicinally effective, I’ll never know. But I have also had cases in which homeopathics were remarkably effective.

This has been especially true with babies and animals, and these are cases we could assume are relatively free from the influence of the placebo effect since the recipients are presumably unaware that they’re getting medicine. In particular, I have repeatedly had the experience of giving homeopathic teething tablets to babies that were inconsolable, and within minutes they were peaceful and sleepy. As a parent, I don’t care what the mechanism is as long as it’s safe and it works.

The safety factor is significant, particularly for children, pregnant women, and elderly or frail people. Not only are homeopathics virtually free of side effects, they also tend to have zero “load” on the system. That is, they don’t make you feel like you’re on a drug. Sometimes this may come at the expense of strength (e.g., homeopathic Chamomilla doesn’t approach the potency of Xanax), but there are cases when the top priority is a clean experience. I find this to be especially true in anxiety, when making someone feel drugged can occasionally intensify the anxiety.

Have you tried homeopathy? What did you think? Share with us in the comments section. I would love to hear about your experience.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => Homeopathy: What Is It and Does It Work?

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => homeopathy-what-is-it-and-does-it-work

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_modified_gmt] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8850

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 2

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[1] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3963

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2014-04-01 13:18:04

[post_date_gmt] => 2014-04-01 20:18:04

[post_content] =>

In the past month's series on nutrition, I explained how the manner in which we eat can affect us as much as our food choices can. We looked at the vital roles that cooking and chewing play in digestion, and the importance of eating slowly and not too much. And I described the digestive tract from the mouth to the stomach. I think it’s important that everyone understands at least the basics of how their organs work, so let's look at the rest of the digestive tract this time.

Although we may have teeth and reality TV, we’re more like worms than we like to think. We’re all just a bunch of cylinders, with a tube of the outside world running through us. Worms put dirt in theirs, we put marshmallows in ours.

After the mouth, esophagus, and stomach, food enters the small intestine, which is about 23 feet long. It's where most nutrient absorption takes place, and all the value of good nutrition hinges on good absorption. At the beginning of the small intestine, a bunch of gastric juice is injected from the pancreas and gallbladder, which neutralizes the acidic food coming from the stomach, and makes the nutrients more absorbable. The pancreas produces a blend of digestive enzymes that break down the different components of food - fat, carbohydrates, and protein. The gallbladder squirts out bile (which is produced in the liver) to make fats absorbable.

The lining of the small intestine is composed of many folds, covered with tiny hair-like protrusions called villi (which are further covered with tinier hairs called microvilli). These greatly increase the surface area of the small intestine to maximize nutrient absorption. Some inflammatory conditions, such as celiac disease (gluten intolerance) and bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine (SIBO) can damage this membrane, leading to malnutrition.

The small intestine is followed by the much shorter but wider large intestine (most of which is called the colon). Food spends a very long time in the large intestine, where water and some remaining nutrients are absorbed, and stool is compacted and waits to be liberated. Finally, the stuff we can’t digest, along with waste products from throughout the body, leaves the rectum as stool. About 60 percent of its dry weight is bacteria.

Where does it come from? Riding along with us in our intestines are about 100 trillion microorganism passengers. There are about 500 different kinds, most of which are bacteria. They’re known as our “gut flora,” and they do all sorts of useful things for us, such as helping us digest things, protecting us from harmful microbes, synthesizing some vitamins, stimulating growth of intestinal cells, and assisting the immune system. We acquire these microscopic pals by eating food that’s contaminated with them or deliberately cultured with them (like yogurt and sauerkraut), and by taking them in supplements known as probiotics.

So, as we’ve seen, our environment (what we select from it based on taste) literally passes through us. We make the outside world into ourselves. It’s a practice worth taking seriously. Besides the healthy eating practices I discussed previously, some of the main factors in good absorption are having enough gastric juice, having healthy gastric membranes, having a strong and healthy population of gut flora, and having a relaxed nervous system.

Cultivating a relaxed nervous system has many additional benefits, so spend time in nature, eat in a calm environment, get massages, meditate, do whatever works for you to become peaceful. As for gastric juice, insufficient enzyme secretion is pretty common. Consider a good digestive enzyme complex, taken at the beginning of a meal. I’ve had at least a hundred patients who have overcome longstanding digestive problems just by supplementing for a while with digestive enzymes. Some people who have trouble digesting fat do well to take a product that also contains ox bile. Finally, promote healthy gut flora by eating live, fermented/cultured foods on a regular basis, and occasionally taking a course of probiotics (especially after using antibiotics).

If you’re interested in learning more about the big picture of eating and nutrition, check out the four week course I developed for The Dragontree, called How to Eat.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => Basic Vehicle Maintenance, Part Three: Know Your Insides

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => basic-vehicle-maintenance-part-three-know-insides

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2014-04-01 13:18:04

[post_modified_gmt] => 2014-04-01 20:18:04

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://www.thedragontree.com/?p=3963

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[2] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 7194

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2018-12-05 19:48:42

[post_date_gmt] => 2018-12-05 19:48:42

[post_content] =>

It’s been a while since I’ve profiled an herb in our newsletter, and I felt inspired to write about rosemary for the holiday season. I have been drawn to rosemary for many years. When I lived in Portland, I passed huge clumps of it on my daily walks. I couldn’t resist running my hands over each one and smelling the piney resin on my fingers.

Rosemary has a long history of medicinal and culinary use, especially in the Mediterranean region. If I had to summarize its properties using only three words, I would say: stimulating, opening, and protecting. Let’s look at these magical qualities.

Stimulating: Traditionally, rosemary has been used to stimulate the mind, the heart, the digestion, the nervous system, and the peripheral circulation. The oil is applied to the scalp to stimulate circulation to the hair follicles and promote hair growth. The herb can be taken as a tea or steeped in wine to improve overall circulation, especially when there are cold extremities, cool and pale skin, low blood pressure, weak digestion, and cardiopulmonary edema.

Rosemary wreaths were worn on the head in ancient Greece to promote sharp thinking and clear senses, and recent research supports this effect. It stimulates and “awakens” a foggy, unclear mind (for this purpose the essential oil can be used in a diffuser or the dilute essential oils applied to the temples). It can be consumed for a sluggish liver and gallbladder with low energy and a yellowish complexion. Similarly, it’s indicated for individuals with poor digestive secretions. In these cases, it stimulates the digestive organs.11

Opening: Traditionally, rosemary was prescribed for an array of conditions that could all be described as forms of congestion or stagnation. These include congestive heart failure, stagnant digestion, muddled thinking, and phlegmy conditions. Rosemary is considered by herbalists to open the heart and blood vessels; to open the digestive tract by moving its contents along, alleviating indigestion and gas (like other members of the mint family); to open the lungs, ears, and sinuses when there is congestion; to open the head (for headaches, especially when there is weak circulation), and to open the senses when they’re impaired.

Animal studies have demonstrated that rosemary is protective against the brain damage caused by stokes; it appears to help “open” the vessels of the brain, leading to less deprivation of fresh blood.10 (It appears, however, that you would have to consume rosemary on a regular basis to achieve this benefit.)

A study of healthy young adults exposed to the scent of rosemary before taking math tests showed that rosemary improved their cognitive performance.5 This effect was attributed to a compound called 1,8-cineole, but rosemary also contains a large quantity of an aromatic compound called borneol. I learned about borneol (called Bing Pian in Chinese) in my studies of Chinese herbal medicine, which classifies it as a substance that “opens the sensory orifices.” That is, it awakens the senses and restores awareness in someone whose consciousness is impaired. Since the borneol we get comes from China and is a white crystalline powder of unknown origin (perhaps synthetic), Americans are generally hesitant to prescribe it for internal use. But in the rosemary leaves, we have a source of borneol that can be safely consumed.

Protecting:

Rosemary possesses several qualities that allow it to protect health, vitality, and freshness. Long valued as a killer of germs and molds, modern research has confirmed that rosemary has antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The herb’s antioxidant compounds protect against oxidative damage to our cells (a major factor in aging and cancer) from exposure to things like UV light, smoke, pollution, fried foods, and household chemicals.

These antioxidant qualities, combined with its antibacterial and antifungal compounds, make rosemary an excellent natural preservative.8 In fact, many of the Dragontree’s body care products contain a small amount of rosemary extract to prolong their shelf life. The rosemary extract inhibits mold and bacterial growth and also protects oils from going rancid.

We’ve recently become aware that high heat cooking, especially of starchy foods, can cause the formation of chemicals known as acrylamides which are likely carcinogenic. New research shows, however, that if rosemary is in the recipe, it significantly lessens acrylamide production.3

Another way in which rosemary is protective is through its anti-inflammatory compounds. While inflammation is a necessary part of healing from an acute injury or infection, chronic inflammation is a different matter altogether. It’s not productive; in fact, it’s a likely player in many degenerative diseases. While anti-inflammatory drugs have drawbacks, the ongoing consumption of foods and herbs that possess anti-inflammatory properties is a safe way to gain some long-term protection.

Research also suggests that rosemary can help protect the liver from damage by certain toxins. A 2016 paper entitled, “The Therapeutic Potential of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) Diterpenes for Alzheimer's Disease,” theorized that compounds from rosemary could be beneficial in the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s, apparently by breaking down or interfering with the formation of amyloid plaques in the brain.2 Further, there has been some promising research on the use of rosemary extracts in the prevention and treatment of cancer.4 However, we're admittedly far from knowing how to utilize rosemary extracts in a consistently effective way for these serious medical conditions.

~

Several times above I referred to the essential oil of rosemary, so I want to share a few words about what this is and how to use it. Essential oils – or volatile oils – are the aromatic substances that give many herbs and flowers their characteristic scent. They’re “volatile” because they evaporate and dissipate quickly. They also have medicinal qualities, both through the effect of the scent itself – what’s known as aromatherapy – and through the pharmacological effects of the complex blend of chemicals they contain, which enter the body through the skin, lungs, and (when consumed) digestive tract.

The therapeutic application of pure essential oils is a medical system in its infancy. It’s barely a “system” at all, in fact – but that’s a topic for another article. While essential oils occur in tiny amounts in most of the culinary herbs and spices we regularly consume – rosemary, cinnamon, thyme, basil, oregano, nutmeg, vanilla, sage, lavender, and peels of orange, lemon, grapefruit, lime, and tangerine – the modern extraction and availability of these oils in pure form allows us to be exposed to them in concentrations and quantities that would never naturally occur. As such, they can be potent to a degree that may be unhealthy. The key is, they should be used very sparingly – not only because it’s not healthy to use large amounts, but because it’s unnecessary. The therapeutic effect occurs with just a tiny bit. So, a bottle should last you a long time.

When oily seeds, nuts, and fruits – such as olive, almond, sesame, safflower, coconut, avocado, walnut, jojoba, and grapeseed – are pressed or processed for their oil, this oil can be called a “fixed” oil. Fixed is in contrast to volatile. These oils are oils in the traditional sense – they’re heavy and fatty, they add richness to foods, and are emollient to the skin. Fixed oils are ideal carriers for essential oils. Typically, you need no more than 2 drops of rosemary oil in a teaspoon (or more) of your favorite fixed oil for application to the skin (such as for hair growth). Or you can make your own rosemary-infused oil by taking 1 cup of rosemary needles, adding 2 cups of oil (ideally a filtered oil or one with minimal flavor of its own), and heating in a covered slow-cooker for several hours on its lowest setting. Then strain it and store it in a jar in a cool, dark place. This oil can be used on the skin or in cooking (don’t use the essential oil in cooking).

There’s a great book for aspiring chefs who endeavor to compose their own dishes, called Flavor Bible, by Karen Page and Andrew Dornenburg. It’s essentially a reference guide which tells you which foods and spices combine well. Following is the very long list of foods that go well with rosemary. Bold entries are recommended by several chefs. Capitalized entries are recommended by an even greater number of chefs. And capitalized entries with a star (*) are what the book refers to as the “holy grail” combinations.

Here they are: anchovies, apples, apricots, asparagus, bacon, baked goods (breads, cakes, cookies, etc.), bay leaf, BEANS (esp. dried, fava, white, green), beef, bell peppers, braised dishes, breads, Brussels sprouts, butter, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, celery, chicken - especially grilled, chives, cream, cream cheese, duck, eggs and egg dishes, eggplant, fennel, figs, FISH - especially grilled, focaccia, French cuisine - especially Provençal, fruit, game: rabbit & venison, *GARLIC, gin, grains, grapefruit juice, zest, grapes, grilled dishes - especially meats & vegetables, herbs de Provence (key ingredient), honey, Italian cuisine, *LAMB, lavender, lemon – juice & zest, lemon verbena, lentils, lime juice, zest, liver, lovage, mackerel, marinades, marjoram, MEATS - especially grilled & roasted, Mediterranean cuisine, milk, mint, mushrooms, mussels, octopus, OLIVE OIL, ONIONS, orange juice, oregano, parsley, parsnips, pasta, pears, peas, black pepper, pizza, polenta, PORK, POTATOES, poultry, radicchio, rice, risotto, roasted meats, sage, salmon, sardines, sauces, savory, scallops - especially grilled, shellfish, sherry, shrimp, soups, spinach, squash – summer & winter, steaks, stews, strawberries, strongly flavored foods, sweet potatoes, swordfish, thyme, TOMATOES, tomato juice, tomato sauce, tuna, veal, vegetables - especially grilled & roasted, vinegar - balsamic, wine, zucchini.

Because of its strong camphorous-piney flavor, it’s natural to think that opportunities to use rosemary are uncommon, but as you can see by that list, it goes well with so many things. I use it at least a few times a week. Combine these culinary occasions with its many medicinal uses and you’ve got a valuable botanical ally. I encourage you to get to know this remarkable plant and use it to spice up your holiday season.

Be well,

Peter

Bibliography

- Eissa, F. A., Choudhry, H., Abdulaal, W. H., Baothman, O. A., Zeyadi, M., Moselhy, S. S., & Zamzami, M. A. (2017). Possible hypocholesterolemic effect of ginger and rosemary oils in rats. African journal of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicines : AJTCAM, 14(4), 188-200. doi:10.21010/ajtcam.v14i4.22

- Habtemariam, S. (2016). The Therapeutic Potential of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) Diterpenes for Alzheimer's Disease. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2016, 2680409.

- Hedegaard RV, Granby K, Frandsen H, Thygesen J, Skibsted LH. Acrylamide in bread. Effect of prooxidants and antioxidants. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008;227:519–525. doi: 10.1007/s00217-007-0750-5.

- Moore, J., Yousef, M., & Tsiani, E. (2016). Anticancer Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract and Rosemary Extract Polyphenols. Nutrients, 8(11), 731. doi:10.3390/nu8110731

- Moss, M., & Oliver, L. (2012). Plasma 1,8-cineole correlates with cognitive performance following exposure to rosemary essential oil aroma. Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology, 2(3), 103-13.

- Murino Rafacho, B. P., Portugal Dos Santos, P., Gonçalves, A. F., Fernandes, A., Okoshi, K., Chiuso-Minicucci, F., Azevedo, P. S., Mamede Zornoff, L. A., Minicucci, M. F., Wang, X. D., … Rupp de Paiva, S. A. (2017). Rosemary supplementation (Rosmarinus oficinallis L.) attenuates cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. PloS one, 12(5), e0177521. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177521

- Naimi, M., Vlavcheski, F., Shamshoum, H., & Tsiani, E. (2017). Rosemary Extract as a Potential Anti-Hyperglycemic Agent: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nutrients, 9(9), 968. doi:10.3390/nu9090968

- Nieto, G., Ros, G., & Castillo, J. (2018). Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis, L.): A Review. Medicines (Basel, Switzerland), 5(3), 98. doi:10.3390/medicines5030098

- Page, K., & Dornenburg, A. (2011). The flavor bible: The essential guide to culinary creativity, based on the wisdom of Americas most imaginative chefs. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

- Seyedemadi, P., Rahnema, M., Bigdeli, M. R., Oryan, S., & Rafati, H. (2016). The Neuroprotective Effect of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Hydro-alcoholic Extract on Cerebral Ischemic Tolerance in Experimental Stroke. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research : IJPR, 15(4), 875-883.

Wood, M. (2008). The earthwise herbal, a complete guide to Old World medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

[post_title] => Making Friends with Rosemary - A Tremendous Botanical Ally

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => making-friends-rosemary

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2020-07-28 21:35:04

[post_modified_gmt] => 2020-07-28 21:35:04

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://thedragontree.com/?p=7194

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 2

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

)

[post_count] => 3

[current_post] => -1

[before_loop] => 1

[in_the_loop] =>

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8850

[post_author] => 1

[post_date] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_content] =>

One of the earliest inspirations that prompted me to go into medicine was a book called The Science of Homeopathy by George Vithoulkas. Of all the many modalities of mainstream and alternative medicine, few are as widely used – or criticized – as homeopathy.

Most other medical systems are heteropathic or allopathic in their approach. Hetero means other or different, allo means opposite, and pathy means suffering or disease. So, both terms mean producing a condition that is incompatible with or antagonistic to the disease process. Today many people use the term “allopathic” in a negative sense to describe mainstream medicine, but if you take an anti-inflammatory herb such as turmeric for inflammation, or an antibacterial such as garlic for an infection, this is allopathic medicine.

Homeopathy is based on the idea that if a particular substance produces a certain reaction (e.g., ipecacuanha causes nausea and vomiting), minuscule quantities of that substance can treat that condition (e.g., homeopathic ipecacuanha alleviates nausea and vomiting). Homeo means like, so homeopathy means “like the disease” and it’s based on the principle that “like treats like.” Some other examples are the use of homeopathic coffee (Coffea cruda) to treat insomnia and agitation, homeopathic onion (Allium cepa) for red and watery eyes and nose, and homeopathic bee venom (Apis) for stings, swellings, and inflammation.

For what it’s worth, not all remedies work this way. In many cases, homeopathic preparations do the same thing the original substance does. The remedy Chamomilla, for instance, is homeopathic chamomile, and like the herb, it is used for digestive and emotional upset. Sometimes homeopathic versions are safer, gentler, more potent, or have a broader range of application. In the case of Chamomilla, it’s also used for teething, ear pain, and menstrual discomfort.

Homeopathic remedies are created through numerous successive dilutions of herbs, minerals, animal parts and occasionally other substances. When the original substance is diluted in ten parts of a solvent (water or alcohol), this is called an X dilution (X being the Roman numeral for ten). When the substance is diluted in one hundred parts of a solvent, this is a C dilution (C being the Roman numeral for hundred). Each time a dilution is made it is shaken in a specific way to transfer the substance to the solvent, and each successive dilution, though chemically weaker, is considered energetically more potent. I made this chart to explain the process:

Many homeopathic remedies are made from highly toxic substances, like arsenic or deadly nightshade. In these cases, the original substance is so highly diluted that the amount of toxin in a resulting pill or tincture is infinitesimal. Often, it’s unlikely that there is even a single molecule of the original substance in the resulting medicine. This is precisely why opponents of homeopathy argue that it’s worthless and call it pseudoscience.

As a scientist, I completely understand this stance, but in my opinion, what occurs in the preparation of a homeopathic remedy is something we don’t yet have the science to explain. I believe the substance leaves some kind of energetic imprint on the solvent it is diluted in. We know from Masaru Emoto’s research on water that various substances and even human intention are capable of leaving a lasting mark on water molecules that’s evidenced in the different forms of ice crystals it forms when frozen. I believe a similar process occurs through diluting and shaking a substance in water, even when the substance is eventually removed.

I must admit, my own experience with homeopathy has been hit-or-miss. I’ve taken numerous remedies that did nothing perceptible. As to whether I chose the wrong remedy or it wasn’t medicinally effective, I’ll never know. But I have also had cases in which homeopathics were remarkably effective.

This has been especially true with babies and animals, and these are cases we could assume are relatively free from the influence of the placebo effect since the recipients are presumably unaware that they’re getting medicine. In particular, I have repeatedly had the experience of giving homeopathic teething tablets to babies that were inconsolable, and within minutes they were peaceful and sleepy. As a parent, I don’t care what the mechanism is as long as it’s safe and it works.

The safety factor is significant, particularly for children, pregnant women, and elderly or frail people. Not only are homeopathics virtually free of side effects, they also tend to have zero “load” on the system. That is, they don’t make you feel like you’re on a drug. Sometimes this may come at the expense of strength (e.g., homeopathic Chamomilla doesn’t approach the potency of Xanax), but there are cases when the top priority is a clean experience. I find this to be especially true in anxiety, when making someone feel drugged can occasionally intensify the anxiety.

Have you tried homeopathy? What did you think? Share with us in the comments section. I would love to hear about your experience.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

Many homeopathic remedies are made from highly toxic substances, like arsenic or deadly nightshade. In these cases, the original substance is so highly diluted that the amount of toxin in a resulting pill or tincture is infinitesimal. Often, it’s unlikely that there is even a single molecule of the original substance in the resulting medicine. This is precisely why opponents of homeopathy argue that it’s worthless and call it pseudoscience.

As a scientist, I completely understand this stance, but in my opinion, what occurs in the preparation of a homeopathic remedy is something we don’t yet have the science to explain. I believe the substance leaves some kind of energetic imprint on the solvent it is diluted in. We know from Masaru Emoto’s research on water that various substances and even human intention are capable of leaving a lasting mark on water molecules that’s evidenced in the different forms of ice crystals it forms when frozen. I believe a similar process occurs through diluting and shaking a substance in water, even when the substance is eventually removed.

I must admit, my own experience with homeopathy has been hit-or-miss. I’ve taken numerous remedies that did nothing perceptible. As to whether I chose the wrong remedy or it wasn’t medicinally effective, I’ll never know. But I have also had cases in which homeopathics were remarkably effective.

This has been especially true with babies and animals, and these are cases we could assume are relatively free from the influence of the placebo effect since the recipients are presumably unaware that they’re getting medicine. In particular, I have repeatedly had the experience of giving homeopathic teething tablets to babies that were inconsolable, and within minutes they were peaceful and sleepy. As a parent, I don’t care what the mechanism is as long as it’s safe and it works.

The safety factor is significant, particularly for children, pregnant women, and elderly or frail people. Not only are homeopathics virtually free of side effects, they also tend to have zero “load” on the system. That is, they don’t make you feel like you’re on a drug. Sometimes this may come at the expense of strength (e.g., homeopathic Chamomilla doesn’t approach the potency of Xanax), but there are cases when the top priority is a clean experience. I find this to be especially true in anxiety, when making someone feel drugged can occasionally intensify the anxiety.

Have you tried homeopathy? What did you think? Share with us in the comments section. I would love to hear about your experience.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => Homeopathy: What Is It and Does It Work?

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => homeopathy-what-is-it-and-does-it-work

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_modified_gmt] => 2022-11-04 22:53:33

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://thedragontree.com/?p=8850

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 2

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[comment_count] => 0

[current_comment] => -1

[found_posts] => 25

[max_num_pages] => 1

[max_num_comment_pages] => 0

[is_single] =>

[is_preview] =>

[is_page] =>

[is_archive] => 1

[is_date] =>

[is_year] =>

[is_month] =>

[is_day] =>

[is_time] =>

[is_author] =>

[is_category] => 1

[is_tag] =>

[is_tax] =>

[is_search] =>

[is_feed] =>

[is_comment_feed] =>

[is_trackback] =>

[is_home] =>

[is_privacy_policy] =>

[is_404] =>

[is_embed] =>

[is_paged] =>

[is_admin] =>

[is_attachment] =>

[is_singular] =>

[is_robots] =>

[is_favicon] =>

[is_posts_page] =>

[is_post_type_archive] =>

[query_vars_hash:WP_Query:private] => 66db2b85c5ed1300bc20d1bb8d380ee2

[query_vars_changed:WP_Query:private] =>

[thumbnails_cached] =>

[allow_query_attachment_by_filename:protected] =>

[stopwords:WP_Query:private] =>

[compat_fields:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => query_vars_hash

[1] => query_vars_changed

)

[compat_methods:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => init_query_flags

[1] => parse_tax_query

)

)

Cart

Cart