WP_Query Object

(

[query] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 39

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 3542

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

)

[query_vars] => Array

(

[category__in] => Array

(

[0] => 39

)

[post__not_in] => Array

(

[0] => 3542

)

[posts_per_page] => 50

[ignore_sticky_posts] => 1

[orderby] => desc

[_shuffle_and_pick] => 3

[error] =>

[m] =>

[p] => 0

[post_parent] =>

[subpost] =>

[subpost_id] =>

[attachment] =>

[attachment_id] => 0

[name] =>

[pagename] =>

[page_id] => 0

[second] =>

[minute] =>

[hour] =>

[day] => 0

[monthnum] => 0

[year] => 0

[w] => 0

[category_name] => ayurveda

[tag] =>

[cat] => 39

[tag_id] =>

[author] =>

[author_name] =>

[feed] =>

[tb] =>

[paged] => 0

[meta_key] =>

[meta_value] =>

[preview] =>

[s] =>

[sentence] =>

[title] =>

[fields] =>

[menu_order] =>

[embed] =>

[category__not_in] => Array

(

)

[category__and] => Array

(

)

[post__in] => Array

(

)

[post_name__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__in] => Array

(

)

[tag__not_in] => Array

(

)

[tag__and] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__in] => Array

(

)

[tag_slug__and] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__in] => Array

(

)

[post_parent__not_in] => Array

(

)

[author__in] => Array

(

)

[author__not_in] => Array

(

)

[search_columns] => Array

(

)

[suppress_filters] =>

[cache_results] => 1

[update_post_term_cache] => 1

[update_menu_item_cache] =>

[lazy_load_term_meta] => 1

[update_post_meta_cache] => 1

[post_type] =>

[nopaging] =>

[comments_per_page] => 50

[no_found_rows] =>

[order] => DESC

)

[tax_query] => WP_Tax_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

[0] => Array

(

[taxonomy] => category

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 39

)

[field] => term_id

[operator] => IN

[include_children] =>

)

)

[relation] => AND

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

[0] => wp_term_relationships

)

[queried_terms] => Array

(

[category] => Array

(

[terms] => Array

(

[0] => 39

)

[field] => term_id

)

)

[primary_table] => wp_posts

[primary_id_column] => ID

)

[meta_query] => WP_Meta_Query Object

(

[queries] => Array

(

)

[relation] =>

[meta_table] =>

[meta_id_column] =>

[primary_table] =>

[primary_id_column] =>

[table_aliases:protected] => Array

(

)

[clauses:protected] => Array

(

)

[has_or_relation:protected] =>

)

[date_query] =>

[request] =>

SELECT SQL_CALC_FOUND_ROWS wp_posts.ID

FROM wp_posts LEFT JOIN wp_term_relationships ON (wp_posts.ID = wp_term_relationships.object_id)

WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.ID NOT IN (3542) AND (

wp_term_relationships.term_taxonomy_id IN (39)

) AND ((wp_posts.post_type = 'post' AND (wp_posts.post_status = 'publish' OR wp_posts.post_status = 'acf-disabled')))

AND ID NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('','employee')

AND `post_id` NOT IN

(SELECT `post_id` FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE `meta_key` = '_pilotpress_level'

AND `meta_value` IN ('' )))

GROUP BY wp_posts.ID

ORDER BY wp_posts.post_date DESC

LIMIT 0, 50

[posts] => Array

(

[0] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3833

[post_author] => 5

[post_date] => 2014-03-12 14:29:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2014-03-12 21:29:52

[post_content] =>

I’ve noticed a lot of tired people this week, people crippled by Daylight Savings Time’s new bright and early wake up hour. It can be a hard adjustment for our bodies to make – and it’s only an hour! As humans, we tend to like stability and routine, interspersed with variety and spontaneity, and the perfect balance is largely dependent on our constitution.

As an Ayurvedic practioner and teacher I’ve found that one of the most useful applications of doshic theory for my students is an understanding of the different ways each constitution relates to change. They’re able to apply this to their routine – and also use it with their partners, employees, employers, children and friends.

There are three doshas: Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. Each represents a group of mental, emotional, and physical qualities, and everyone has a blend of all three. Most people have one or two doshas that are predominant, and some people have one dosha that is especially prominent. This article won’t even come close to giving you a complete education on the doshas, but I want to convey enough of this wisdom to give you a sense of how each one relates to change.

Change is inevitable. It’s up to us to create a healthy relationship to it.

Vata’s Relationship to Change

When Vata dominates someone’s constitution, they’re highly changeable. In fact, they will tend to desire change even when changing things may not be the best option. They don’t stay hooked into any single version of reality for long. They move, travel, change subjects, switch careers, and alter hair colors as often as my iPhone autocorrect thinks I’m trying to say ‘ducking.’ Vatas are often

compelled to change, whether they like it or not. Their energy can come in surges and then disappear, their digestion can be fast and then slow, their enthusiasm can wax and wane. While change is inevitable for Vata, the more healing thing for them is to have periods of structure and stability. This will help focus their scattered minds and give them the ability to put all of their creative energy toward something of substance.

Pitta’s Relationship to Change

Pittas are results driven, so if change will get them closer to their goal then they’ll get on board readily and with gusto in the new direction. However, if they don’t see the change as beneficial for their desired end result, they will resist it with fiery passion. The most useful tool for Pittas in dealing with change is to take a little time to process and plan the change before acting. It can be hard for Pittas, who tend to be fast thinkers and fast responders, to allow for a little space in a situation they think is faulty. Doing this will give them perspective – and be gentler on those who may be affected – before they move fervently with the change or react hastily in opposition to it.

Kapha’s Relationship to Change

Kaphas dislike change. I’d say that they hate change, but they aren’t likely to express emotion in such a strong manner. So, I’ll stick with dislike. Kaphas are prone to staying in crappy situations, because they would rather have the crappy situation they know than the unknown future that change would bring. When forced to change, Kaphas are very slow to adapting. But, once they adapt, they’ll be loyal and dedicated to the new situation.

For Kaphas, regularly changing certain elements of their routine is helpful for maintaining balance. Varying things like food choices, exercises, clothing, or route to work – trying new things – can help them remain flexible. They also do well with lots of physical movement and mental stimulation, this breaks up and moves stuck energy and makes it easier for them to adapt to change.

You can use this ancient wisdom to help work through changes in your family or business. If you live or work around a Pitta, don’t take it personally when they decide without warning that a major overhaul is necessary. Help them get some perspective and cool down a bit before making any big changes. If you have a Kapha kid or employee, giving them a lot of time to get used to a change before it’s implemented can help ease them into it and relieve some of the resistance they are likely to feel. If you have a Vata partner, knowing about their variability may help you be more tolerant when they change the subject in mid-sentence, or seem unable to make up their mind about anything.

How do you react to change? What can you do to help maintain a healthy balance?

Your loving Pitta,

Briana

[post_title] => How to you deal with change?

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => deal-change

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2014-03-12 14:29:52

[post_modified_gmt] => 2014-03-12 21:29:52

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://www.thedragontree.com/?p=3833

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[1] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 7874

[post_author] => 5

[post_date] => 2020-05-05 18:50:00

[post_date_gmt] => 2020-05-05 18:50:00

[post_content] =>

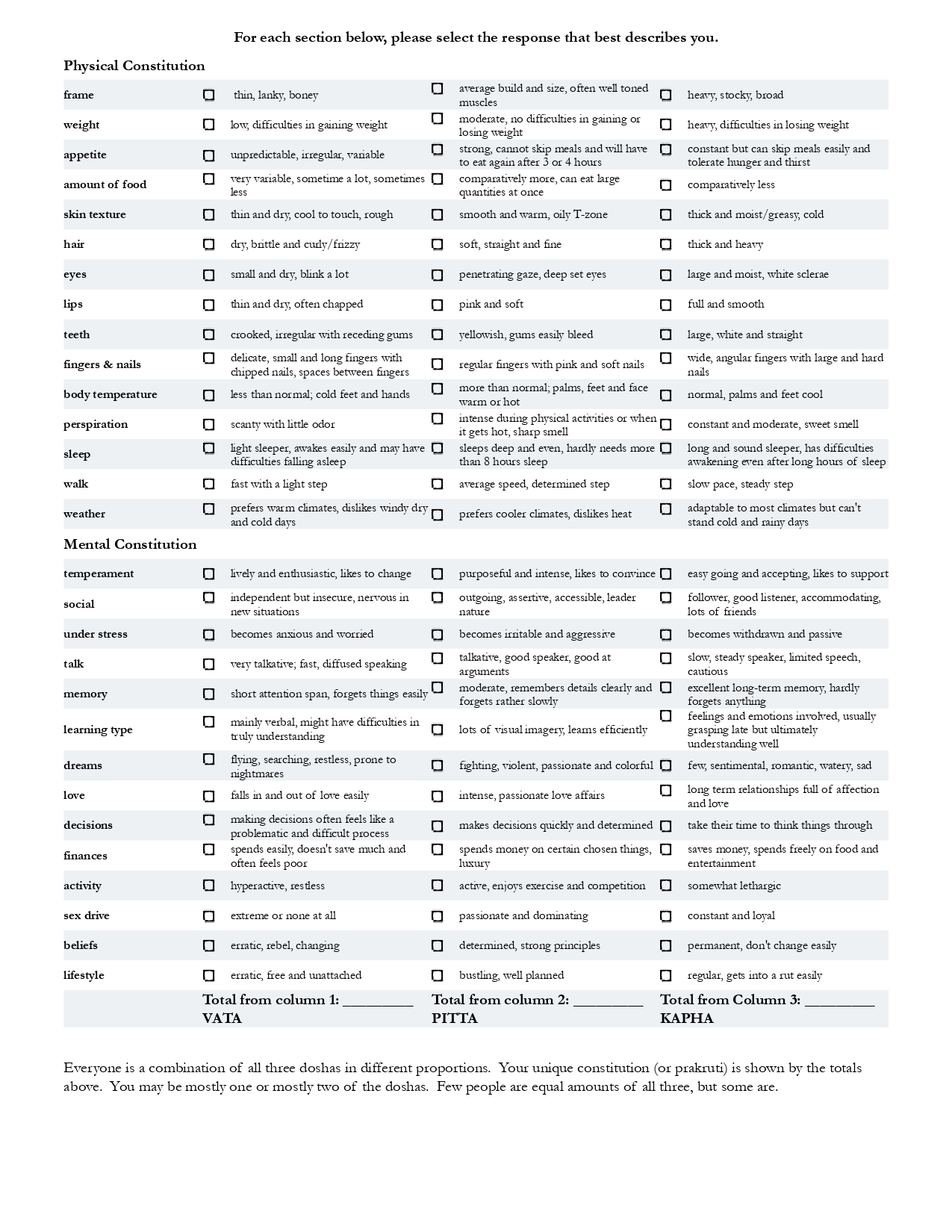

The traditional healing system of India, Ayurveda has an over 6000 year history of effectively bringing into balance the body, mind, and soul. It is founded upon the unchanging, universal principles of the natural world. As the science of life, Ayurveda goes well beyond the treatment of disease, to guide us in living life fully and achieving our potential.

At the core of Ayurvedic philosophy is the concept of the three doshas, the vital energies that make up our physical constitution and are evident all around us.

Knowing your doshic constitution provides you with an understanding of your basic physical and psychological nature, and helps you tailor a personal diet and lifestyle that maintains optimum health and peace of mind.

Only a qualified Ayurvedic practitioner can accurately assess the exact balance of Vata, Pitta, and Kapha energies in your physical constitution; however, it is possible to get some idea from a simple self-test.

Click to Download PDF

Click to Download PDF

If you're ready to dive into how to best support your unique doshic constitution, catch a re-play from our co-founder, Briana Borten a Clinical Ayurvedic specialist, in her class on the best type of massage for your doshic type.

[embed]https://www.facebook.com/TheDragontree/videos/691899801561365/[/embed]

[post_title] => The Dragontree Doshic Constitution Quiz

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => dosha-quiz

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2020-05-12 21:01:59

[post_modified_gmt] => 2020-05-12 21:01:59

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://thedragontree.com/?p=7874

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 10

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[2] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 4471

[post_author] => 3

[post_date] => 2014-09-23 10:07:01

[post_date_gmt] => 2014-09-23 17:07:01

[post_content] =>

As we approach fall, it’s a good time to discuss seasonal junctions. Both Ayurvedic and Chinese systems of medicine see the changes of seasons as times when we are more susceptible to being thrown out of balance as our body is challenged to adapt to the shift. Ayurveda has a saying that “diseases are generated at the junctions of the seasons.” Other junctions are also challenging, with the challenge generally proportional to the magnitude of change. Svoboda writes, “Ovulation and menstruation are the ‘joints’ of the menstrual cycle, dawn and dusk are the joints of day and night, and adolescence and menopause are the junctions of life.” If you have kids, you know that the “joints” of the day are the times you’re likely to have trouble, and if you’re clever, you find ways to make these transitions easy, such as the ever-popular “five more minutes until we’re leaving.”

Depending on where you live and your personal constitution, or prakruti (which I discussed in last week’s article), different seasons and junctions will be challenging for different people. For example, because spring tends to be wet, moving into this season means taking on more kapha. This will be most difficult for those who already have a lot of kapha in their constitution. Traditionally, kapha types might be prescribed some therapeutic vomiting to make the transition easier, whereas pitta types should require only moderate cleansing, and vata types would do well with the most gentle and slow cleansing.

I don’t know about you, but some therapeutic vomiting would really hit the spot, right? No, these days in the West, we prefer more pleasant medicine, ideally in gummy form, and we engage in therapeutic vomiting only after an excess of margaritas. Luckily, there are gentler ways to reduce each of the doshas (also explained last week), and when it comes to management of the seasonal junctions, the most natural is to adjust one’s diet and activities from season to season. Kapha is cold and moist, so, during the late winter and spring, we should employ anti-kapha measures. Pitta which is hot, should be controlled in the summer. And vata, which is dry and cold, should be reduced in the fall and early winter. Meanwhile, whichever dosha or doshas are predominant in your constitution require year-round management.

The junction at hand, from summer to fall, typically means an increase in vata, due to the drying out and loss of leaves, the approaching cold, and the reduced moisture-holding of cooler air. But in a place like the Pacific Northwest, this is the beginning of the long rainy season, and thus, an increase also in kapha, so it’s an especially challenging transition. In Portland and Seattle, it’s getting both dryer and moister. How do you manage it? Well, it’s a balance, and it depends partly on which of these factors affects you more.

If you don’tlive in a place where it’s about to get very wet, you have only to deal with an increase in vata, which can be balanced with nourishment, stability, consistency, warmth, and moisture. Vata is characterized by extreme changeability, and more change tends to make people in this season (and especially those with vata as a predominant constitutional factor) feel out of whack. So, making your routine as consistent as possible can really help: going to bed and waking up at the same time each day, eating at the same times each day, moving your body about the same amount and exerting roughly the same amount of energy each day, and having other self-care practices that you do each and every day. If you’ve been eating lots of fresh, raw summer produce, you can begin the transition to cooking more of your food. Warm, cooked food should form most of your diet in fall and winter.

Massage is excellent for reducing vata. Ghee and sesame oil are especially good for vata, both eaten and applied to the skin. A wonderful daily practice, especially if you have a vata constitution, have dry skin, or an overactive mind, is self-massage. You can obtain some sesame oil (not the toasted kind) and simply get naked and rub the oil into your skin from head to toe. Then, if you like, jump in the shower and rinse off, but without using soap, so that you finish with skin that’s still moist.

If you live in a place where the rainy season is beginning, it’s a good idea to begin your kapha-reducing routine now. Like vata, kapha benefits from heat, so spending time in a sauna can be good for both doshas (just don’t get dehydrated or sweat profusely, since this can exacerbate vata). Movement is essential to keep damp kapha weather from causing stagnation in the body, but since this is also a vata season, make sure your movement is even, smooth, not excessive, and at roughly the same times each day.

As for food in places with a damp autumn, there are not many things that are good for treating both kapha and vata. Since vata is dry, it benefits from moistening and oily foods – exactly the kinds of things that worsen kapha. Some of the only overlap occurs in the realm of spices, most of which tend to be good for both doshas, including these in particular: garlic, ginger, bay leaf, black pepper, caraway, cardamom, cinnamon, coriander, fenugreek, nutmeg, and saffron. Try incorporating them liberally into your fall and winter cuisine.

Wishing you a harmonious junction,

Dr. Peter Borten

[post_title] => The Joints of Life

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => closed

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => joints-life

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2014-09-23 10:07:01

[post_modified_gmt] => 2014-09-23 17:07:01

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://www.thedragontree.com/?p=4471

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

)

[post_count] => 3

[current_post] => -1

[before_loop] => 1

[in_the_loop] =>

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3833

[post_author] => 5

[post_date] => 2014-03-12 14:29:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2014-03-12 21:29:52

[post_content] =>

I’ve noticed a lot of tired people this week, people crippled by Daylight Savings Time’s new bright and early wake up hour. It can be a hard adjustment for our bodies to make – and it’s only an hour! As humans, we tend to like stability and routine, interspersed with variety and spontaneity, and the perfect balance is largely dependent on our constitution.

As an Ayurvedic practioner and teacher I’ve found that one of the most useful applications of doshic theory for my students is an understanding of the different ways each constitution relates to change. They’re able to apply this to their routine – and also use it with their partners, employees, employers, children and friends.

There are three doshas: Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. Each represents a group of mental, emotional, and physical qualities, and everyone has a blend of all three. Most people have one or two doshas that are predominant, and some people have one dosha that is especially prominent. This article won’t even come close to giving you a complete education on the doshas, but I want to convey enough of this wisdom to give you a sense of how each one relates to change.

Change is inevitable. It’s up to us to create a healthy relationship to it.

Vata’s Relationship to Change

When Vata dominates someone’s constitution, they’re highly changeable. In fact, they will tend to desire change even when changing things may not be the best option. They don’t stay hooked into any single version of reality for long. They move, travel, change subjects, switch careers, and alter hair colors as often as my iPhone autocorrect thinks I’m trying to say ‘ducking.’ Vatas are often

compelled to change, whether they like it or not. Their energy can come in surges and then disappear, their digestion can be fast and then slow, their enthusiasm can wax and wane. While change is inevitable for Vata, the more healing thing for them is to have periods of structure and stability. This will help focus their scattered minds and give them the ability to put all of their creative energy toward something of substance.

Pitta’s Relationship to Change

Pittas are results driven, so if change will get them closer to their goal then they’ll get on board readily and with gusto in the new direction. However, if they don’t see the change as beneficial for their desired end result, they will resist it with fiery passion. The most useful tool for Pittas in dealing with change is to take a little time to process and plan the change before acting. It can be hard for Pittas, who tend to be fast thinkers and fast responders, to allow for a little space in a situation they think is faulty. Doing this will give them perspective – and be gentler on those who may be affected – before they move fervently with the change or react hastily in opposition to it.

Kapha’s Relationship to Change

Kaphas dislike change. I’d say that they hate change, but they aren’t likely to express emotion in such a strong manner. So, I’ll stick with dislike. Kaphas are prone to staying in crappy situations, because they would rather have the crappy situation they know than the unknown future that change would bring. When forced to change, Kaphas are very slow to adapting. But, once they adapt, they’ll be loyal and dedicated to the new situation.

For Kaphas, regularly changing certain elements of their routine is helpful for maintaining balance. Varying things like food choices, exercises, clothing, or route to work – trying new things – can help them remain flexible. They also do well with lots of physical movement and mental stimulation, this breaks up and moves stuck energy and makes it easier for them to adapt to change.

You can use this ancient wisdom to help work through changes in your family or business. If you live or work around a Pitta, don’t take it personally when they decide without warning that a major overhaul is necessary. Help them get some perspective and cool down a bit before making any big changes. If you have a Kapha kid or employee, giving them a lot of time to get used to a change before it’s implemented can help ease them into it and relieve some of the resistance they are likely to feel. If you have a Vata partner, knowing about their variability may help you be more tolerant when they change the subject in mid-sentence, or seem unable to make up their mind about anything.

How do you react to change? What can you do to help maintain a healthy balance?

Your loving Pitta,

Briana

[post_title] => How to you deal with change?

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => deal-change

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2014-03-12 14:29:52

[post_modified_gmt] => 2014-03-12 21:29:52

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://www.thedragontree.com/?p=3833

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

[webinar_id] => 0

)

[comment_count] => 0

[current_comment] => -1

[found_posts] => 11

[max_num_pages] => 1

[max_num_comment_pages] => 0

[is_single] =>

[is_preview] =>

[is_page] =>

[is_archive] => 1

[is_date] =>

[is_year] =>

[is_month] =>

[is_day] =>

[is_time] =>

[is_author] =>

[is_category] => 1

[is_tag] =>

[is_tax] =>

[is_search] =>

[is_feed] =>

[is_comment_feed] =>

[is_trackback] =>

[is_home] =>

[is_privacy_policy] =>

[is_404] =>

[is_embed] =>

[is_paged] =>

[is_admin] =>

[is_attachment] =>

[is_singular] =>

[is_robots] =>

[is_favicon] =>

[is_posts_page] =>

[is_post_type_archive] =>

[query_vars_hash:WP_Query:private] => 2a01b35b259a59bbc7bc710ba8ca414d

[query_vars_changed:WP_Query:private] =>

[thumbnails_cached] =>

[allow_query_attachment_by_filename:protected] =>

[stopwords:WP_Query:private] =>

[compat_fields:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => query_vars_hash

[1] => query_vars_changed

)

[compat_methods:WP_Query:private] => Array

(

[0] => init_query_flags

[1] => parse_tax_query

)

)

Cart

Cart