A couple weeks ago, I wrote about the differences between acupuncture and “dry needling” to alleviate pain, and in that article I explained a bit about the phenomenon of myofascial trigger points. After I said I believe these are the cause of most of the physical pain humans experience, a number of readers asked me to explain more. For the science lovers out there, I’m going to dive deeper this week.

Besides the most common forms of pain, like lower back and headaches, I’ve had patients with digestive problems, sinus congestion, chest pain, ear ringing, numb hands, painful intercourse, acid reflux, vision changes, and other health issues that were eventually discovered to be due to myofascial trigger points. I believe everyone should know about them and how they work – it could save us a lot of time and worry.

Basically, a trigger point is a small, irritable region in a muscle (or the surrounding connective tissue – “fascia”) that stays stuck in a contracted state, making the muscle fibers taut. This can cause reduced muscle strength and range of motion, pain, numbness, itching, and other forms of dysfunction. Sometimes a trigger point feels like a palpable nodule or “knot,” but to untrained fingers they’re often tricky to find.

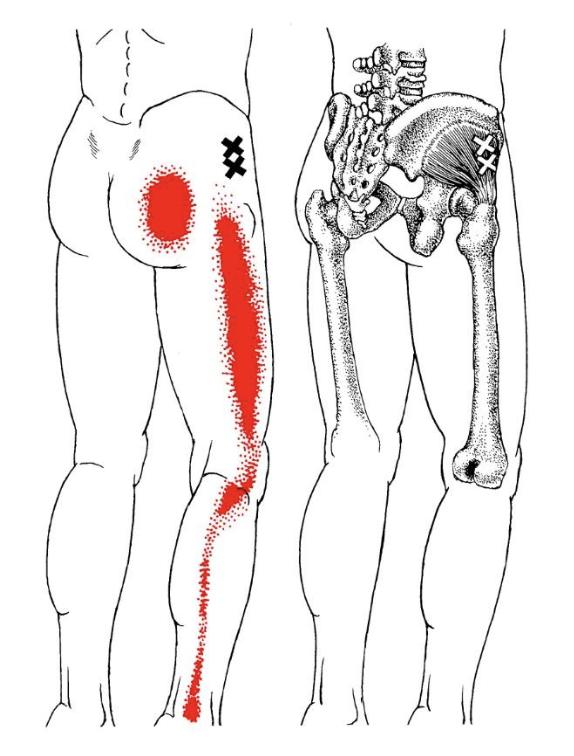

A unique property of trigger points is that they’re able to produce symptoms in other parts of the body – from a few inches to a couple feet away. For instance, there’s a trigger point that can form in the soleus muscle of the calf that’s capable of producing pain in the lower back. For this reason, the work of Janet Travell, MD and her colleague David Simons, MD, was groundbreaking. For each muscle in the body, they mapped where trigger points tend to form and what kinds of symptoms they cause.

If you were experiencing pain along the outside of your leg, you might assume that something was wrong with that part of your leg, perhaps with the often-tight iliotibial band (IT band). But this diagram might be helpful. The X’s show where trigger points can occur in a muscle called gluteus minimus above the hip socket. The red shading shows the potential areas of pain that can result. You might not suspect this muscle because, as you can see, there’s no pain at the site of the problem!

There are a handful of mechanisms that can promote trigger point formation, such as irritation of nerves, chronic organ problems, nutritional deficiencies, and autoimmune disorders. Most often, though, the cause is trauma to our connective tissue. When a muscle is strained by being worked too hard, too fast, or beyond its natural range, there is frequently a sort of “recoil” that occurs as segments of the muscle fibers bunch up and remain that way.

This is especially common when someone works out without warming up; when someone does a very ambitious workout after not having exercised for a long time; when someone makes a sudden movement (like reaching out to catch something or trying to stop oneself from falling); and especially when someone does any of the above when in a state of diminished resilience (e.g, when stressed, upset, sleep deprived, eating poorly, etc.).

Even more commonly, the trauma is a form of “postural stress” that’s demanding on muscles in a way that’s difficult to perceive at the time – such as doing the same relatively motionless activity (like sitting at a desk or driving) for hours, days, months, or years. One possible mechanism is known as the “Cinderella hypothesis.” During static muscle exertion – holding a position for a long time, as dentists, musicians, typists, and others engaged in precision handwork do – the body tends to engage a certain group of small muscle fibers, called Cinderella fibers because they’re put to work first and are the last to be disengaged. Even though they’re not doing heavy lifting, these muscle fibers (often in the neck, shoulders, back, and forearms) are continually activated and overworked, which makes them susceptible to trigger point formation.

Whatever the cause, the result is that eventually the muscle never completely relaxes. Muscles are composed of numerous parallel fibers that work together to shorten (contraction of the muscle) and lengthen (the return of the muscle to its relaxed state). Within each of these fibers are many end-to-end contractile units called sarcomeres, and in the case of a trigger point, a group of sarcomeres gets “stuck” in a shortened state. This makes the affected fibers taut and often “stringy” feeling.

To make matters worse, the contracted region clamps down on tiny blood vessels causing local ischemia (inadequate blood supply), reducing in-flow of fresh, oxygenated blood and out-flow of toxins. This leads to a localized hypoxic state (not enough oxygen). The tissue pH changes, local metabolism is impaired, and fluid and waste products tend to build up in the area. This combination of factors ultimately activates pain receptors – it starts to hurt – and when this happens you use the affected muscle less.

Instead, you overload “synergists” – nearby helper muscles. The body makes the surrounding musculature tense as a protective mechanism. Meanwhile, there’s a disruption of the balance between the affected muscles and their “antagonists” – those muscles that lengthen when the primary muscles shorten and vice-versa (for example, the triceps is an antagonist of the biceps). Altogether, this restricts natural movement of the original muscle, which just perpetuates the imbalance. Finally, with longstanding trigger points, the body may deposit gooey lubricant compounds called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) between these triggered muscle fibers, resulting in a gummy lump called a “myogelosis.”

The good news is that there are now books, charts, online tools, and practitioners that can help track down likely trigger points that may be implicated in your discomfort. I have such a tool in my online pain relief course, Live Pain Free, and I teach many approaches for deactivating trigger points.

The most basic methods involve simple mechanical disruption of this holding pattern. First, drink some water if you’re not well hydrated. Second, you or a friend can methodically feel around (ideally guided by a trigger point chart) for points that are sore, and ideally that reproduce the very sensation you’ve been experiencing. Third, maintain firm pressure on the epicenter of the point (with a finger, elbow, ball, or other tool) for about half a minute, consciously breathing into the area and intending to let it go, until there’s a palpable release. Then move on to all the other nearby points that are tight and tender and do the same.

This approach is called ischemic compression. By compressing the tissue enough to block blood flow, the body responds with reflex vasodilation, meaning it opens these vessels and flushes the tissue with a dramatic increase of blood. This will usually produce a significant improvement in the pain or dysfunction, though it will typically return sooner or later. These points tend to go from being active trigger points to “latent” trigger points, which have a certain “memory” (not the good kind of muscle memory) and are capable of getting reactivated. For this reason, persistence is important. The best results come from working on a trigger point consistently – usually from one to several short sessions per day (or less frequent if the sessions are intense) – and continuing for a while even after everything seems better.

As I said, this is a most basic approach, and while it’s often effective, sometimes a more nuanced intervention is required. There are many techniques that build on compression. We can replace fixed pressure with slow, deep strokes in the direction of the muscle fiber, as if re-lengthening this segment. We can work the trigger point back and forth across the direction of the muscle fibers. We can combine pressure on the trigger point with engagement of the affected muscle or antagonistic muscles. We can combine manual work on trigger points with topical herbs and/or internal herbs and nutrients that improve circulation and reduce inflammation. We can utilize release points on the same acupuncture meridian as where the trigger point occurs – or complementary points on other parts of the body. And more.

If all of this sounds interesting and relevant to you, I encourage you to do a little research. It might well be the end of a problem you thought had no solution. And if you need more guidance, check out my online course, Live Pain Free, where I go deeper into trigger points and much, much more to help people get out of pain of all kinds.

While I said I believe trigger points are the cause of most of our physical pain, I think it’s worth mentioning there are usually even deeper causes, such as stress and withheld emotions, poor body mechanics, dehydration, and an inflammatory diet. Holistically addressing these issues will lead to a more complete resolution of the condition. Always look at the big picture.

Be well,

Dr. Peter Borten

Cart

Cart